In a 2015 study, Norwegian and Swedish scientists proposed that fluctuations in the climate of the Central Asian steppes caused the region’s rodent population—probably gerbils and marmots in particular—to crash. That, in turn, may have forced fleas that carried the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which causes plague, to leave their rodent hosts and find new places to live, such as camels and their human owners. After several years of flea relocation, as the scientists’ theory goes, it took another decade for the caravans to gradually advance the plague westward, until it reached the edge of Europe.

Kaffa, a Crimean Black Sea port now known as Feodosia, “seems to be the jumping off point for the primary wave of the medieval Black Death from Asia to Europe in 1346-7,” Welford says. “Genoese or Venetians left Kaffa by boat, infected Constantinople and Athens as they made their way to Sicily and Venice and Genoa. But I suspect [Black Death] also made it to Constantinople via an overland route.”

One famous 14th-century account claimed that plague was introduced to Kaffa deliberately, through a Mongol biological warfare attack that involved hurling plague-infected corpses over the city’s walls.

Black Death Spreads East to West, And Then Back Again

Whether that actually happened, the plague eventually became a disaster in the East as well as in the West. “It killed off many of the Mongol rulers and other elite, and weakened the army as well as the local economies,” explains Christopher I. Beckwith, a distinguished professor at Indiana University Bloomington, and author of the 2011 book Empires of the Silk Road. It’s estimated that the Black Death killed 25 million people in Asia and North Africa between 1347 and 1350, in addition to the carnage in Europe.

A 2019 study by German researchers genetically linked the Black Death to an outbreak that occurred in 1346 in Laishevo in Russia’s Volga region, raising the possibility that the disease may have spread from Asia by multiple routes.

In any case, when the Black Death reached Europe, it attacked a population that already was weakened and malnourished by the brutal nature of the feudal economy.

“I think a good argument can be made that [Black Death] hit at a time when the health of the poor was compromised by the stress of famines, poverty and the very nature of serfdom,” Welford says.

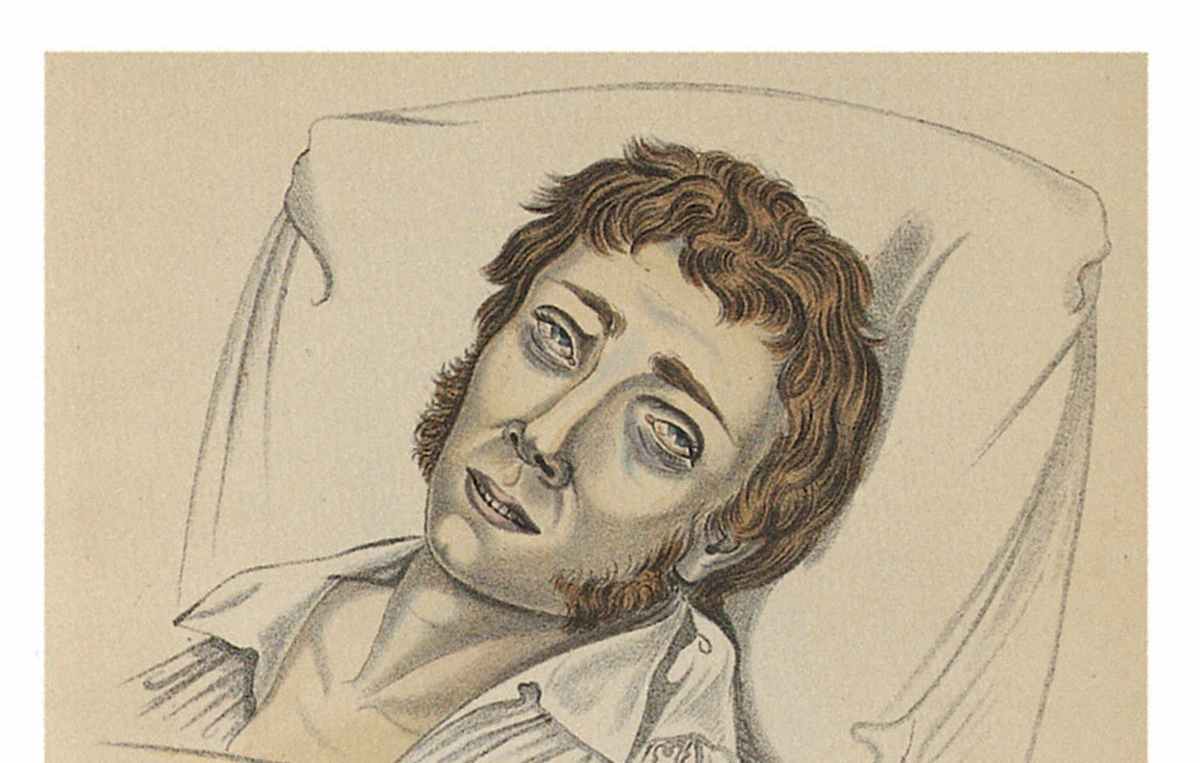

In The Decameron, written in 1352, Giovanni Boccaccio describes the Black Death, which reached Florence in 1348. Victims first developed a swelling in their groins and armpits, after which the disease “soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, then minute and numerous.”

Between March and July of that awful year, Boccaccio noted that more than 100,000 of the city’s inhabitants died, their bodies piled outside doorways. Grand palaces and stately homes where the nobility and their servants had dwelled were left empty, so that the city was “well-nigh depopulated.”